A collection of short essays on my recollections of growing up in the Sierra foothills in the 1950s.

By Tim Konrad

Everyone has their own favorite stories to tell, and my father was no exception. He loved to recount events from his past, often after he’d had a few shots of bourbon to loosen his tongue. Among the tales from his younger days that he was fond of narrating was one about the deer that jumped over the moon.

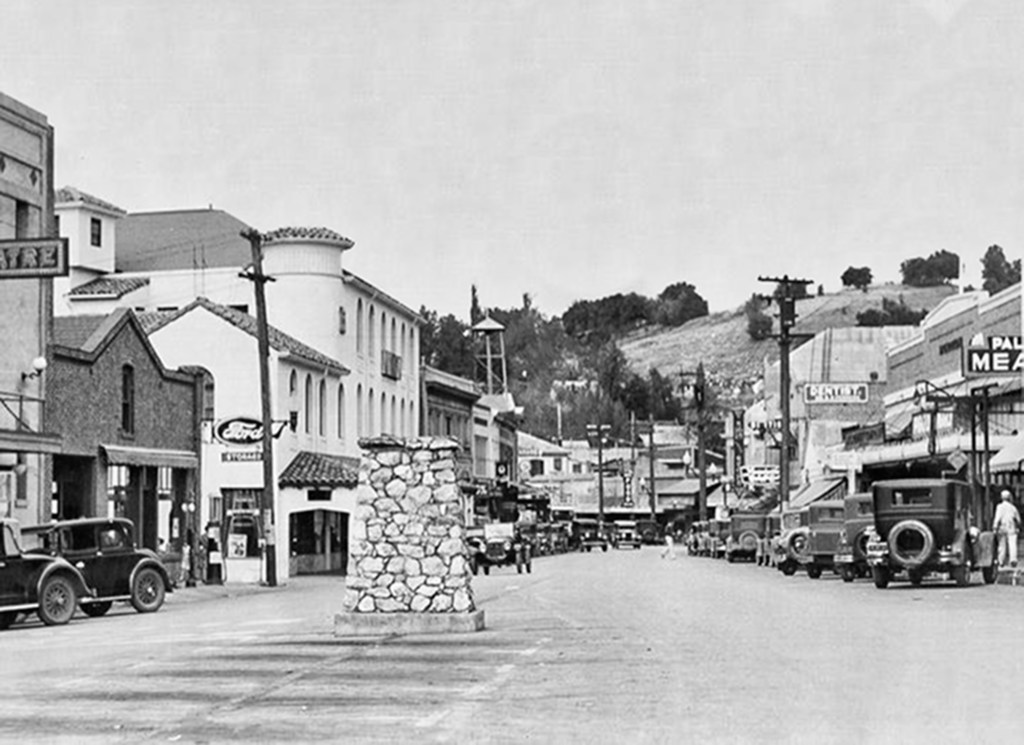

Back in the 1920s, when my family was living at the Von Tromp Mine, northeast of Columbia, they owned a roadster made by the Moon Motor Car Company. One warm summer’s evening, my mother and father and my Aunt Dorothy and Great Aunt Vida struck out for town leaving the roadster’s soft top folded back so they could enjoy the moonlight filtering through the trees.

As they were descending the grade on Italian Bar Road just above the old brewery, a deer leaped without warning from the bank overhanging the roadway, passing within inches of everybody on its way down the hill.

Another story my Dad recalled from the 1920s was about a visit he and his brother, Jack, made to a bar in Angel’s Camp.

The place had been packed with celebrants, in town to participate in the annual festivities inspired by Mark Twain’s famous story “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras.”

Many of those present were taking full advantage, my uncle included, of the liberal dispensation of libations flowing uninterruptedly from the bar. Before long, my uncle became engaged in a scrap with an Angel’s Camp boy.

My storied uncle was never one to shy away from a good fight. He had once broke the nose of a young man he’d been scrapping with in Sonora. Unfortunately, for Jack, the young man’s father had turned out to be a supervisor with the Civilian Conservation Corps. This man was a person of considerable influence; because of his standing in the community, the matter achieved outsized attention. As a result, my uncle was sentenced to a term of several months in the county jail.

In his fight with the fellow from Angel’s Camp, Jack was unaware his opponent had a twin brother who was also involved in the melee. No sooner would Jack knock the man down than his brother would rise in his stead, eager to continue the fracas. My uncle, unsuspecting and undaunted, continued to hold his own.

Meanwhile, the bystanders were becoming more and more agitated, incensed that this ‘stranger’ was getting the better of his two opponents. My father took notice of the group’s growing unease. The foothill towns displayed a stronger sense of community back then, and inter-community rivalry was common. Observing that the lion’s share of those assembled to witness the event were, naturally, rooting for the twins and were not likely to take their defeat lying down, my Dad saw no reason to waste time pondering the plausible implications of his observation. Grabbing Jack, he hustled him away to their car, whereupon they made a hasty retreat back to Tuolumne County.

As noted above, rivalry between communities was not uncommon in days past, but its rough edges were often smoothed over and made to appear more civilized through the medium of athletic competitions like baseball and football. Prior to the rise of professional sports franchises, minor league baseball and football were an essential part of life in the foothills and beyond. These days, local rivalries are mostly seen in high school and college sports.

The rules were a little different in those days too. Contrary to the current emphasis in the sport of football concerning the long-term effects of concussions on players, my Uncle Jack told of a football game he played in as a young man in which one of his team-mates—a big Indian fellow—played a whole quarter with a broken shoulder. Such behavior, while viewed as evidence of manliness in those days, would be neither advisable nor possible in this age of frivolous lawsuits.

***

Sometimes community rivalry can take on a deeper tone. A life foolishly lost at an E Clampus Vitus gathering in the 1970s led to a decade of hard feelings between rival communities and a several-years suspension of Clamper festivities that wasn’t lifted until it was agreed that no more guns or knives would be allowed at gatherings.

The event, or “Doins,” as they are referred to in Clamperdom, took place at the former site of a placer mining operation at the foot of Big Hill east of Columbia. The victim was the cook for the gathering and was from a prominent Angels Camp family with roots going back to the Gold Rush. The fellow with the gun was a member of an old-time Columbia family with similar tenure on the south side of the river. The latter man hadn’t meant any harm and believed he was shooting blanks when he shot the cook in the stomach at near point-blank range as he was going through the food line.

My father, his friend “Bing,” and I had just been through the line and were sitting down eating around 50 feet away when we heard the gunshot. I remember seeing a crowd gather around the food line as confusion spread and medics were called. The hapless fellow was taken to hospital but his injuries were too severe to stop the blood loss and, late that night, he succumbed. The Columbia man was convicted of manslaughter.

Justice is a bittersweet solution that does nothing to ease the pain of the loss of a loved one.

The owner of the property where the ‘Doins’ took place, a man named Bartell Kress, himself had a colorful history. As the story was told to me, this fellow purchased a brand- new Cadillac from the local General Motors dealer with the stated intention of paying it off in installments. Some months later, when the sum of his missed payments triggered alarms concerning his true intentions vis a vis his loan, he began receiving demands for payment from the lender threatening to repossess the vehicle if his arrears weren’t addressed.

Not a person to be outdone, so the story went, and inclined by nature not to yield to pressure of this sort, Mr. Kress devised a novel way to conceal the Caddie’s whereabouts while guaranteeing the failure of any future attempts at repossession. With the aid of his D-8 Caterpillar tractor, Kress dug a hole deep enough to conceal the vehicle, at an undisclosed location, and then dropped the Cadillac into it and covered it up.

***

The foothills were full of characters back then—in some cases tough individuals who had their own ideas about how to deal with life’s little problems. One such person was the owner of a famed and fabled downtown Sonora saloon. When I was a boy I recall going inside the place and seeing large photographs on the walls—mural sized but crude in quality—that depicted large pits dug in the ground that were filled with dead cattle—the result of an extermination campaign designed to eradicate an outbreak of hoof and mouth disease back in the 1920s.

The owner of this establishment had the misfortune, one evening, to be shot in the face by an unnamed assailant. Owing more to luck than anything else, the wound did not prove fatal. The police had their hands tied because the victim refused to identify the shooter, so the case remained, and still is to this day, unsolved. The owner was quoted at the time as having said he would deal with it in his own way. The man is now long since passed, but I had the good fortune to chat with his daughter a few years ago. She would not speak to the identity of the assailant except to say her father “dealt with it.”

Another shooting incident at a different downtown Sonora bar in the same general time period involved a disagreement over a card game gone wrong. The guilty party, angered after he was caught cheating, stormed out of the place, only to return a short while later armed with a pistol; he then walked up behind the man who’d caught him cheating and, after the fashion of the man who shot Wild Bill Hickock, also during a card game, shot him in the back of his head at point-blank range.

Imagine this fellow’s surprise when the victim rose up out of his chair and proceeded to take matters into his own hands. It turned out the pistol was only a 22 caliber–not an efficient choice for a murder weapon–and his intended victim was an extremely large Mi-Wok man with an unusually thick skull. The projectile deflected when it encountered the man’s skull, circling to the left under the skin and exiting from the back of his head. A witness to the incident told me, years later, that the offender received a good thrashing from his intended victim for his transgression.

There were a couple of MiWok families from the town of Tuolumne who produced young men of exceptional size, averaging 6’ 5” and weighing between 280 and 320 pounds. I once watched one of these behemoths climb over three booths of diners at a local restaurant in response to a challenge from an antagonist. On another occasion, I witnessed a group of these individuals cruising main street in Sonora on a Sunday afternoon with the tapper from a keg of beer visibly protruding above the back seat of their vehicle.

The local police chose discretion with these folks whenever possible, for obvious reasons. They pulled over the car in front of a liquor store on the south end of town, one patrol car in front and another behind the partiers, to keep them contained within their vehicle while a solution was negotiated—take the party somewhere else or face arrest.

To be continued: